Zion National Park

Of the many visitors to the Southwestern corner of Utah, the vast majority have Zion national park on their to-do lists. Known for its massive walls of Navajo Sandstone, big wall climbing routes and for being the center of the canyoneering universe, this gem of Utah is visited by millions of people a year from all over the world. The vertical exposure of Navajo sandstone faces in Zion canyon itself are generally conceded to represent the tallest sandstone cliffs on the planet. This deep defile on the edge of the Colorado plateau has been carved over the millennia by the surprisingly placid Virgin river, and upstream by its many tributaries. This system of drainages and its surrounding highlands represent a virtual labyrinth of peaks and passages that offer a lifetime of exploration.

Geology:

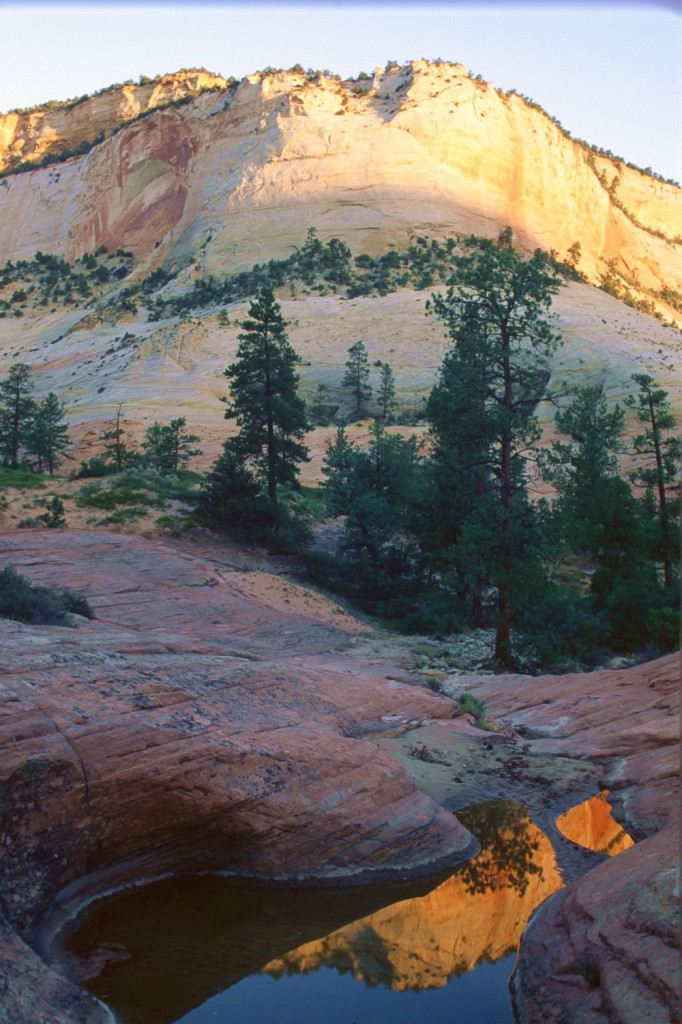

Navajo Sandstone is perhaps the most scenic type of rock in the world. It can vary in its color from red, pink, orange, salmon and brown. It is also extremely beautiful because of the way it erodes, leaving deep canyons, elephant skin textures, arches, moki balls and hoodoos. 170-183 million years ago, this stone was a massive desert of sand that spanned from Colorado to California. It was brought there by winds over a more than 10 million year period. At times, the direction this wind came from would shift. These shifts left obvious changes in the direction of this rock’s strata. Look for these sudden changes on Zion’s slickrock terrain and canyon walls. Horizontal lines can be seen in the stone, then a few feet above that, they suddenly shift to diagonal lines. Eventually these layers were covered by water which leeched minerals into them. These minerals, along with immense pressure from overlying layers cemented this late Triassic sand into a rock. As the ocean receded and tectonic movements raised the entire Colorado Plateau to higher elevations, every rainstorm and period of snowmelt contributed to an already relentless process of erosion. Desert sandstones are notoriously soft (compared to other types of stone) and erode at a geologically fast pace, especially under flowing water. The source of the North Fork of the Virgin river is Navajo lake, high on the Markagunt plateau. This alpine lake lies at 9,000 feet above sea level, and roughly 40 miles upstream from Zion canyon, which is below 5000 feet above sea level. It is this extremely steep gradient along with the malleability of the soft stone which create the vertical wonders of Zion canyon. The Virgin river is perennial and each year transports thousands of tons of rock, sand and debris to ever lower elevations, with much of this material composed of rock types that are harder than the sandstone. Now you essentially have a belt sander carving the river floor deeper and deeper every year as the harder stones and pebbles grind away the softer sandstone. This erosion’s effects are multiplied several days a year when flash floods carry much larger rocks and significantly more sediment in general through the canyon. Many other canyons and washes also feed into the Zion canyon, which do not feature year around running water, but still flood several times a year, and are eroded deeply by the same forces as the main canyon. Between these canyons and washes lie high areas where the stone still has the shape of sand dunes. Small pockets of rock that contain more iron oxide are stronger and erode more slowly than the surrounding rock, allowing them to stay intact and form Moki balls, arches and hoodoos on the higher areas of the rock. The diversity of scenery within Zion is staggering. Water, wind and time have truly made this place breath-taking.

Biology:

Zion’s ecosystems vary from riparian habitats below 4,000 feet elevation with deep canyon shade, allowing frogs, snails, cotton wood trees and ferns to flourish, to semi-desert highlands at over 8,000 feet, with ponderosa pines, spruce, fir and even aspens. This variety of habitats allows for a wide variety of life to inhabit Zion. This park boasts over 900 species of plants, nearly 300 species of birds, 78 mammalian species, 44 species of reptiles and amphibians, and 8 species of fish (according to the parks website:http://www.nps.gov/zion/naturescience/index.htm). From rodents and Beavers, to Cougars, Deer, Foxes, Desert Big Horn Sheep and Ring-Tail Cats, the types of mammal species here are extremely diverse. Birds range from Canyon Wrens, Herons and Wild Turkey to Turkey Vultures and California Condors. Reptiles and amphibians include Collared Lizards, Horned Toads, several types of rattle snakes, common fence lizards, frogs and many more.

History:

Zion’s human history dates back thousands of years to nomadic tribes who followed large prey animals across the Americas. The pleistocene extinction then wiped out nearly all large animals here, requiring a new way of life. Between approximately 9,000-2,000 years ago, , the desert archaic culture flourished, eating smaller prey as well as foraging plants. Eventually the Ancestral Puebloans (or Anasazi) adopted farming techniques and thus settled in areas semi-permanently as in Zion canyon. Here they farmed the river bottom, built storage granaries for their excess crops in hard-to-reach alcoves, saving it for hard times, and built elaborate dwellings on the surface and underground from wood, rock and clay. As the landscape became increasingly desertified an increasing number of droughts eventually caused the Anasazi to abandon their crops and move to wetter environments more suitable for farming around 1300. The open niche was filled by various Paiute tribes who were more nomadic and dependent on hunting and foraging and less reliant on the little riverside farming that they practiced. Beginning in the 1700’s, pioneers, trappers and settlers began to push natives out of these ideal farming locations and eventually, with the arrival of the Mormon settlers in the mid 1860’s, the native Americans were displaced from the choicest locations for agriculture. The rugged canyon was farmed by settlers who lent their names to many of the formations like Heaps canyon for decades until it was turned into a national monument in 1909 and a national park in 1919.

Hiking Trails:

Trails Map:

http://www.nps.gov/zion/planyourvisit/hiking-in-zion.htm